By Lucy Berrington, MS, Vital Signs editor

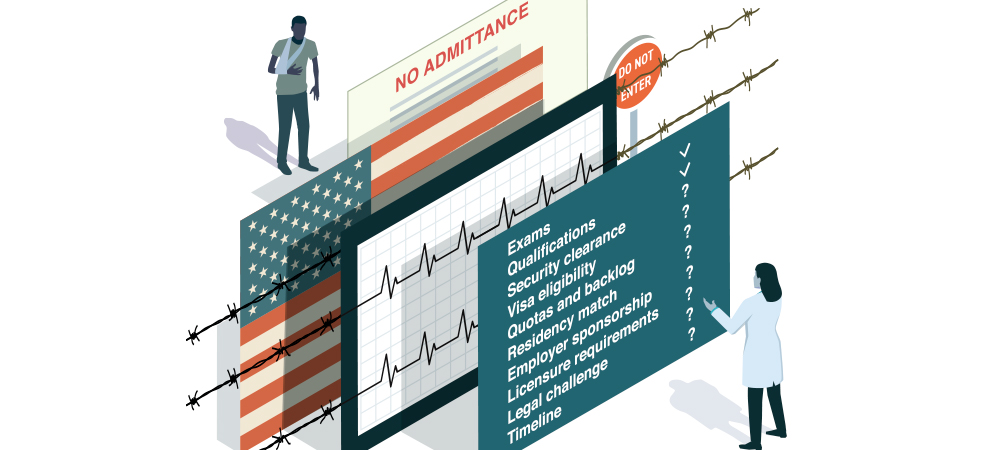

Illustration by Chris Twichell.

Illustration by Chris Twichell.

Recent developments in immigration policy and rhetoric are influencing immigrant patients’ ability and willingness to access health care, according to physicians and other stakeholders. Patients are weathering a “climate of fear,” says Sarah L. Kimball,

MD, an internist and co-director of the Immigrant Health Center at Boston Medical Center. “There’s no doubt in my mind that my patients are changing their health care utilization based on fear. We see it every day.”

Increasingly, immigration status is being considered a social determinant of health because of its contribution to uneven health outcomes. Immigration status is almost certainly affecting patients and care delivery at practices and hospitals across the

Commonwealth, say physicians and attorneys who spoke to Vital Signs. “We know that even if we as providers are not thinking about our patients’ immigration status, our patients are thinking about it,” says Dr. Kimball.

In 2018, the MMS House of Delegates resolved to advocate for legislative/ regulatory changes that will protect the civil rights, safety, and well-being of all patients by emphasizing a boundary between immigration enforcement and health care.

Public Charge Raising Alarm

A proposed change to the “public charge” rule would deny green cards to certain immigrants who access publicly funded benefits including health care — or are perceived as likely to access those benefits in future. In a statement in August, Maryanne C.

Bombaugh, MD, president of the MMS, said, “I am as fearful as I am certain that

the administration’s public charge regulation will have direct and dire consequences for our most marginalized and at-risk patients.”

The rule change has since been halted by federal judges in three states; as Vital Signs went to press, a temporary injunction was put in place. But even before the change was due to take effect, its implications and complexity were frightening

broad communities into forgoing health care, physicians and attorneys say. “The public charge rule I think has been made intentionally complicated to drive people out of the health care system,” says Dr. Kimball.

The revised rule could dissuade up to half a million Massachusetts residents from accessing benefits, including health care plans and care, says Fiona S. Danaher, MD, a pediatrician based in Chelsea, which is home to communities of people from Central

America, and co-chair of the MGH Immigrant Health Coalition. “The proposal issued last fall suggested that the change could apply more broadly, and that misinformation has everyone scared. People are pulling out of health benefits, food stamps, WIC

[a nutritional program for women and children, not part of the public charge], and public housing, including those who are not affected by the rule.”

The impact of the proposed change extends far beyond those actually targeted by the law, says Andrew P. Cohen, supervising attorney at Health Law Advocates, a firm based in Boston that helps low-income residents access health care. “There’s no doubt that

many people are chilled from accessing public benefits, but very few immigrants who have access to benefits are implicated under the rule. Physicians should know that when patients are afraid of coming to see them, that fear may be misplaced.” Most

immigrants will be exempt from the rule even if it goes into effect as written, he says, including the vast majority of those who are eligible for MassHealth.

Clinical Dilemmas

The politics of immigration are leaving patients and physicians struggling with conflicting information and seemingly impossible dilemmas. One of Dr. Kimball’s patients had been granted asylum, so he was not subject to the public charge rule, yet falsely

believed he had to stop getting food stamps. But if the public charge rule goes into effect, another of her patients, a woman from Honduras, is truly at risk of being denied a green card as a result of using Medicaid.

“None of us ever want our patients to choose between their immediate safety and their long-term health,” says Dr. Kimball. “That’s what the public charge rule is asking people to do. It’s hard for a primary care provider to worry about patients’ high

blood pressure, which may harm them in 10 years, versus their safety at that moment.”

Fear as a Health Risk Factor

Patients are also aware of expanded deportation and detention programs, including detention centers on the southern border that have become associated with family separation and inadequate health care and hygiene provisions. “Prior to this administration

I hadn’t had patients put into detention,” says Dr. Kimball. The scope and apparent randomness of such enforcement instigate more fear, she says.

Tiffany Joseph, PhD, associate professor of sociology and international affairs at Northeastern University has, since 2012, been researching the impact of documentation status on health care access in Massachusetts. In interviews with providers and patients

this year, she heard repeatedly that following immigration raids or threats of raids, fewer patients show up for medical appointments in those communities. “They’re concerned about intersecting levels of government, whether ICE can see that they went

to a doctor’s appointment,” she says. Health care facilities are “sensitive locations” — outside the jurisdiction of immigration authorities — but patients are concerned about encountering law enforcement or ICE outside or en route to hospitals and

clinics, as has been reported around Boston’s courthouses and schools, she says. The MMS is advocating to honor and protect health care facilities as sensitive locations and for safe access regardless of immigration status.

The stress related to immigration status is spreading beyond those communities, says Dr. Danaher, who serves on the MMS Committee of Violence Intervention and Prevention. “People are feeling increasingly targeted for their immigration status and their

race. We see that in the increase in racially motivated school bullying, the El Paso shooting targeting Latinx people. It’s not just immigrants but entire populations feeling very threatened. It’s hard for providers to keep on top of the ways this

is affecting their patients. I have patients in my office crying because they’re worried about what will happen to them and their kids.”

Matilde Castiel, MD, commissioner of public health in Worcester, practices in a substance use disorder treatment program. “We refer patients to other care, but they’re afraid, so they tend not to follow up,” she says. “The level of stress and anxiety

is very high. One patient’s temporary status is up and he doesn’t know what to do. All of his family is American, and he’s the breadwinner, so what happens to his kids if he has to leave? It comes down to structural racism.”

Matilde Castiel, MD

The spreading of fear can compound existing health and social problems, as well as generate new ones, she says. Worcester has high rates of youth homelessness, addiction and overdose, hunger, obesity, and other risk factors. “We have a tough time identifying

the people who need the most help because they are afraid to come out [of hiding], often because of their immigration status,” says Dr. Castiel. “This makes the situation worse.”

Increasingly, researchers are measuring the impact on health. A JAMA study in July suggested that among teen children of Mexican immigrants in California, fear and worry associated with immigration policy and rhetoric since 2016 were associated

with higher anxiety levels, sleep problems, and blood pressure changes. “Other studies have shown lower birth weights and more pre-term deliveries,” says Dr. Danaher. “Providers should be aware of this broader public health issue because it’s affecting

what they’ll see in the exam room.”

Health Insurance and Life-Saving Treatment

Meanwhile, a presidential proclamation set to take effect in November requires some visa applicants to prove their access to health insurance or demonstrate sufficient assets to pay their future health care costs. That shift targets “family reunification,”

when the spouses or family members of legal US residents seek to move here.

Another policy shift, in August, threatened adults and children who were in the US specifically for life-saving health care with imminent deportation. Dr. Danaher was among the physicians who testified on Capitol Hill about the likely consequences for

patients, and persuaded the administration to reverse the decision.

Yet such advocacy success is not always replicable. “That was a specific situation because the affected parties [including children with cancer] were so sympathetic,” says Mahsa Khanbabai, an immigration attorney based in Greater Boston. Advocating against

the changes to this program consumed her and other attorneys for several weeks, diverting resources away from the other challenges facing legal immigrants.